In 1901 when the March winds blew, my father was born to Lura and Watson just thirteen months after the birth of his older brother Clifford. Wilford Edison Park lived all his life in the shadow of this noisy and exuberant brother, loved him and called for him at the end. Even his name 'Wilford' reflected the first-born's name of Clifford. Wilford was shy and withdrawn, slow to talk and much favored by his maternal grandmother Cutler because he was born on her birthday. She bestowed upon him the middle name of Edison which, being Scottish, she pronounced with a long E.

Wilford and Clifford spent their young lives on the hot sandy farms and in the villages round and about Fairground, that tiny cross roads village in Oxford County.05 There the dusty days of summer stretched long into the year and the almost snow-less winters passed with studies, church socials and sometimes skating on the ice puddles. Mostly there was work. Springs brought early mornings when crystal drops beaded cobwebs and spiked grasses, cool to the feet and the hands holding the alder switch that urged the cows home along the fence for first milking. It was a time of ploughing straight and true rows and of planting and birthing, and hopes that this year would be more prosperous than last. The summers were a scramble of chores; hedges edging the long curves of the driveway to be clipped, the white washing of the decorative rocks and the insides of the outbuildings; and hoeing, acres of hoeing under

With the coming of fall, the harvest and the summing-up began. The silage was shot into silos and stomped into place, the corn was thrown into slatted 'vee' shaped racks for drying and future shucking; and the pigs were slaughtered for home-ground and canned-in-fat sausage patties. But it was during the hoeing that the probing questions niggled most and it was then that as a young lad Wilford placed his fate in the hands of Jesus. This gentled him, and never did his spirit waver from this acceptance through all of the tragedies of his life, tragedies from which he believed would spring something good. Later however, his acceptance of Jesus as Savior bestowed its own unhappiness when Wilford discovered that several of his children would not rest in heaven as he defined it, having never accepted his view of religious salvation.

Though without funds or background and with little encouragement from his father who had expended his ambition on his eldest son Clifford, still Wilford pursued his dreams of becoming a doctor. The boys were sent off to high school, each in turn to Vienna, a village six miles distant where they boarded their weeks through and walked home to hay or to quarter seed potatoes for planting on weekends.

Wilford saw no future in farm life and as young as sixteen he dreamed his encompassing dream of giving his life to the betterment of mankind in some foreign land as had Albert Schweitzer. These

Wilford was older than most to go to the little high school in Vienna with its thirty students.05a He was needed for farm chores while Clifford, the one destined for the ministry, studied. But Wilford did finish those three years; at nineteen he was still shy of a senior matriculation which was not offered in so small a setting. With characteristic single mindedness Wilford settled on the University of Toronto's six year medical program as his future and it was with trepidation that he approached the registrar without the necessary entrance requirements: no senior matriculation, no money, a farm kid adrift in the city, armed with a dream.

The University may have sensed his determination; or perhaps it was the frayed cuffs that his grandmother had attempted to turn; or fervent

In a small garret on Grosvenor street the two brothers lived, schooling and studying in their separate fields, boiling water on a hot plate, eating apples and porridge.06 Bread soaked in milk with brown sugar was one of their staples. There was little time for friends except for a slight acquaintance with some girls down the street at the Christian Centre and a Jewish lad, one of the few allowed admittance to medical school. Wilford was too shy and poor to contribute much to any relationship. Being narrow in his tolerance for sin and frivolity and short of funds he was hardly sought out for company.

When did he ever see my mother, Lila? She, meantime was going to business college while living with Orpha Naish, one of her married sisters, the one who late in life passed along the few treasured tales I have. At some point Lila must have moved to Toronto too because we know that she worked at Eaton's store and sang in the Timothy Eaton choir. Did she move there because Wilford was there or because it was the big city with a future? She loved to dance and party but could don the Christian mantle with some reverence when necessary. Lila Marshman was slight

Wilford and Lila were married in September of his fifth year at the University of Toronto.07 She was twenty-five and had done some amount of living on her own. It was a small wedding, a little sheer flapper dress of cream pastel, with brimmed cloche, a handful of roses, and friends from the Christian Centre; they continued to live on in the garret on Grosvenor street with its hot plate and pail of cooking water on the chair beside, and a few pots hung on the wall. Lila neglected to announce her new status at work because that would have meant certain job loss.

She cried most of the night before she was married. Her sister Orpha told me so. And she told me too that there was another man, a farmer, who loved her and who never married. When I asked my aunt why my mother had chosen my father, she replied that it was because he was a doctor, but we'll never know. As always, perhaps as all women, she chose carefully the father of her children and she chose an interesting and productive life with dreams of far missions and perhaps she loved his vulnerability and his determination and his gentleness too.

Had she always known she would marry him as he had her? Lila was slender and fine boned, beautiful as her mother before her, with a sense of style controlled but free. I've heard it said that she was vivacious and giving, a perfect helpmate for my withdrawn father. They bought Limoges china for twelve to cement their dreams.

But what did she trade? For years after marriage Lila would regularly visit her sisters alone so she could dance to the village fiddles. And she would tuck the sticky dinner dishes in the oven to avoid chores and nick aspirins from the dispensary to send to needy relatives, or so I'm told. But she was loved and perfect my father said. This view was also expressed by my Uncle Clifford and Grandfather Park. And I was supposed to grow up to be like her but of course I never could. The closest I could come was to have fresh flowers stationed at the center of the table as she did. She may have needed them sometimes when she reflected on her life.

Where did my father learn to cook? Like other young students my father took to the road to sell Wear-Ever pots in the hope of making enough money for the next year's schooling. Quickly he learned the tricks; never dwell on the fact that you are a hungry medical student, never waste time on women who you suspect have no intention of buying. He held group demonstrations in homes which were followed with personal visits; he was good at those presentations. He could fry eggs and pancakes without fat in those aluminum pans by first placing a scrap of paper in the pan and assessing the temperature of the pan by the browning of the paper. I've seen him do it many times though I never could achieve success and I suspect most purchasers couldn't either. He cooked cakes and omelet's, stews and dumplings and delighted in his culinary achievements which I suspect, far surpassed those of any of his future wives though I'm not sure about

It must have been about the time of the wedding that the camera was purchased. The few earlier photographs of them as youths were tattered and thumbed, not of a set, carried by lovers, impossible to tell by which from the faded writing on the back. Now the chronicle began of their lives together, their special times, which were well documented in photographs with the appropriate years and names in my father's spiky script.

After the wedding, squeezed into a student vacation, there were visits to family, both sides who had not attended. So things continued on as dreamed and the pictures say they were happy.

Wilford graduated a year later near the top of his class, with pennies in the bank and a Phi Beta Kappa key. One graduation picture of the two of them together bears the script 'looking into the future' as he gazes to the left and Lila straight ahead grinning.09

Directly after graduation in June his internship began. It was to have been for a year but in May he was struck with rheumatic fewer, in retrospect probably inevitable in a streptococcus laden hospital environment. He had enjoyed interning and fancied himself a superior diagnostician but now it was over. As yet there were no sulphonamide drugs available and the use of penicillin lay well in the future. There was no money and there would be no mission fields.

With the coming of late spring he asked to be transferred home. There was no place else to go. He could neither stand nor walk. They placed him on a stretcher in a train boxcar and with my mother beside him they moved slowly off, back to the farm on the dirt road in Fairground. The photos stop here for a year and a half. It was a time that stretched from hour to hour. In the beginning he slept in a small tent pitched in the shade of a spruce tree in the front yard.10 With the coming of cold nights his father hoisted him on his still strong shoulders and carried him up the steep and narrow stairs to the bedroom. There the feather down ticking was a shaken fresh mound on the bed, and the wall paper smelled of damp plaster, and the washbasin always needed filling. And the fevers came and went leaving him drenched to her touch, and clammy cold and burning. She washed him and fed him, lay with him when he slept. The hours moved into days. Summer ended but still the fevers came, creeping and slashing. Often the heart raced into the night, only gentled by first light. Lila was there when he reached for her. The family adored her and needed her, my grandfather told me so, many years later. The winter came bringing those dark days which allow the kind of sinking sleep you can't climb out of. With the last of the snows the fevers stopped and they could hope again, though Wilford would be chased periodically by fevers and heart-racings for the rest of his life.

In April, Wilford and Lila again left the farm with the promise of a future. Unshaken in his faith in providence, my father truly believed that his illness had been a holy sign that he was not to mission in far fields using his medical abilities; he was to contribute to goodness on behalf of the Lord close to home as the fates decreed. So began his first trial in the acceptance of his God's wishes with the sure promise that all would be well, and something fine would mature out of misery.

By now they had been married three years and a first medical position materialized. Wilford was offered a job working with Dr. Alexander in Tillsonburg, an unchanging village of perhaps three thousand people set on the flat lands of Southern Ontario. He hoped to become a partner and was sent off to school again in Toronto to learn the mysteries of eye-glass fitting so the office equipment could be used to its fullest. He bought his first car, an unidentifiable model from the photo, his foot placed on the running board to signify ownership. 11 On his return a few months later he found that the envisioned partnership had been sold to a country doctor living in Brownsville, a cross-roads village six miles away. So he began again, this time buying the country practice left vacant in that small village with hospital privileges in Tillsonburg. Wilford was on his own and Lila was pregnant. He opened his office on September 1st, 1929, eight weeks before the great stock market crash. My mother miscarried her first baby.

With the practice came a white clapboard house with a ready made office with slippery black

Immediate additions were made to the office. A sun-reflecting plaque with name and prominent M.D. was affixed to the front entry;13 a shouting tube was run from the front door to emerge near a sleeping ear in the upstairs bedroom; drugs, small vials, microscopes and Bunsen burner were added to make up the dispensary. Mrs. Jacobs in the village was hired to wash bloody towels and bandages in her home and a man who was mentally challenged was hired to mow the lawns.

Most necessities including groceries, boots, meat and postal stamps could be purchased from a building across the road, set high on its basement to accommodate a wagon loading platform. The village's verandahed clapboard and yellow brick homes backed onto fields of corn and fat cows who contributed to the dairy, which nestled concrete-cool and sweet-creamed by the stream. Snakes lived along the stream as well, copper-heads and puff-adders.

Dr. Wilford Park, first opening first office in Brownsville, 1929

There were few patients. Those remaining loyal to the original doctor followed him the six miles to Tillsonburg if transportation was possible. So at first it was emergency work primarily, farm accidents, cuts to be stitched and broken bones to be set, held firm with plaster of Paris, and ear aches through the black nights pulsing with blood rhythms, and the

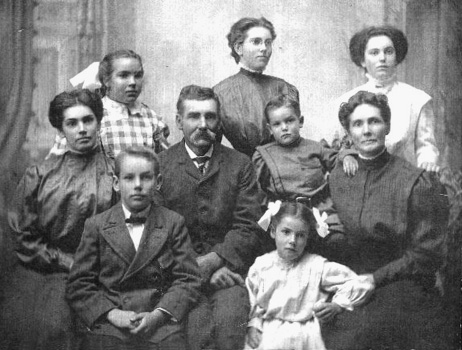

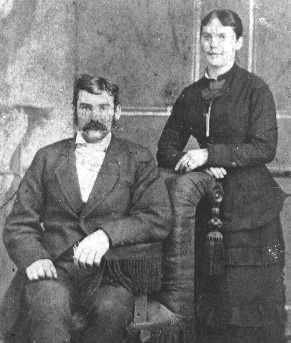

Joseph and Emily Jane Marshman, married 1877, parents of Lila

It was in April of their first year in the village that Lila's grandmother on her mother's side, Emily Marshman, died on her farm near Fairground.15 Death occurred at home with dignity in those days, though

I was conceived in late October of that year, before the frost, when the wild blue asters bloomed. I see my first pictures, occupying my space inside my mother's swollen tummy. My father wrote small poems to me, hoping I would be a girl, a replica of my mother or so he told me later. With the first stirring of life she must have remembered the one miscarried, and grieved for the unrecognized lost one, as all mothers grieve for such losses.

A new car arrived before I did, a Dodge-six is pictured on the first of July, square nosed and pop- eyed bearing the license plate D (for doctor) and the inauspicious numbers 996. The labeling of doctor's plates was discontinued in later years resultant to thefts of the drug laden black bags carried by working physicians at all times. I arrived a few weeks later, and judging from the string of proud pictures, I was much admired.16 They called me Betty, perhaps without realizing it was the fashionable name currently in vogue on the screen. Many girls in my generation seemed to be named Betty. Within the year my

Then the breezes shimmied the purple vetch and bees hummed, prowling the buttercups. And sometimes blackened half-skies to the west grew into churning pyramids boiling and reaching for the stratosphere. And so the bees hurried on prodded by heat and pressure changes.

My father kept bees. Between patients he could be seen in his bee-keeper's head-net and his smoke-can poking and prodding; the colony was never quite sure what to expect.16a However, he knew the garden well. Wild yellow rose bushes clung to the wooden fence that skirted the lane and grape vines wove solid the long bower leading to the outhouse, their notched flat leaves cool against the sun and mysterious in the night. The vegetable garden was examined and tended with care: potatoes and corn were hilled; bugs were picked off leaves and stems; and the hoeing was sure and accurate, skillful in its search for intrusion, slicing at an angle to rough the soil in tune with rhythms of the heart. Wilford had his hoe in his hand the day Lila cried out for him to come.

My doll and I were sitting in the sun on the concrete walkway leading to the grape arbour; we were reaching for dandelions. My mother was poised in the doorway when I heard that primitive cry of fear, low and unmistakable in its demand for me not to move and for my father to come. I saw then what my mother had seen. Two puff adders coiled and upright, heads balanced broad like cobras, waited

My brother, Douglas was born in the winter, a strange pixy creature with large ears, resembling no one. I thought him passable and he didn't cry much. The family rejoiced in the new arrival. My mother's large family of sisters visited often, and in the spring a niece, Maxine came to live and to help while attending the local school. The dog and the cat and the expanding family hummed with a kind of happy frenzy.18 Plans were made to celebrate my third birthday. A wicker doll carriage just my size to push, and a huge doll were purchased and hidden away and my mother anticipated my delight as she brushed my hair from my face in the mornings to be caught in an oval clip with ribbons.19 Doctoring continued at a goodly pace. Babies were born in the homes in the village. Many of them were named Wilford, after my father.

The dangers of childbirth were such that each new arrival and survival cemented a close bond between doctor and mother. He was proud of this in a withdrawn way, tipping his hat when he met an acquaintance but hurrying on sometimes glancing back, never stopping for small talk. He didn't know how to talk small talk.

My mother looked wan and thin in her last pictures taken at the end of May holding my brother and me, the three of us kneeling in the grass smiling directly at my father holding the camera. Two weeks later a copy was sent to her sister, Orpha. On the reverse side was penned a little message which said "It's about time I came to your place." She never did go though. Influenza came stalking and there were no pictures for two months, not till my third birthday, a birthday without her.

It took her nine days to die. Septicemia from a cut finger crept like a black serpent. Those nine desperate days are locked away somewhere in a child's memory, the curtains drawn. The consulting doctors, the care-giving sisters, the hours of quiet prayer and the coming to terms. Lila pleaded with my father not to let her die, my grandfather told me. And Wilford tried in all the ways he knew to get sulpha from France, the new miracle drug of which he'd read, but he couldn't. She must have said good-bye to my brother and me and reached for us one last time and she asked her sister, Orpha to tend us and keep us close.19a Then her acceptance was complete. "Won't Mama be surprised to see me." she said at the last and then she was gone. She'd gone to live with Jesus my

The place of burial was not the bowered grave

yard down the dirt road in Cultus where her parents

and generations of Wilford's family lay.20

No, Wilford

bought an enormous plot in a more upbeat and

perpetually tended area in Tillsonburg, big enough for

at least four, as though founding his own burial

dynasty.21

Comfort came from knowing where we all

would eventually rest, close together under the pale

skies of Southern Ontario laced with trees humming

with cicadas.

Lila Park, 1927, first wedding anniversary

A few hours after my mother died, her niece arrived from Saskatchewan. By train she'd come, our cousin Ethel, anticipating a home, not knowing that the hand of the Lord had struck and her favorite aunt had been taken. She was nineteen and became our nanny, diapering my brother, wiping away my tears.21a She tended us and the household through the next months which stretched to a year and a bit. She tended my father, too, who was often sick with grief and recurring fevers.

I went searching for her when I was older, a whole half century later, hoping to find an answer. My question was a haunting one. It was "Where had they all gone, the cousins, the aunts who'd promised to care for us? Why did I not so much as know their names though my father had tried to maintain a sort of contact through Christmas cards?"

I recognized her when I found her, still a peppery, freckled red head at eighty. It was here that I began to unravel her family's misplaced rages, those choking angers that can never be spewed, only transferred somewhere. Ethel now appeared to distrust my father, and my mother's sister Orpha had reservations too. They blamed him for my mother's death, saying that he didn't get help in time, that she'd died of some kind of curable blood cancer and had been sick for more than a year. She told how he'd refused her own cooking while crumbling his bread in milk for his comfort food, how he'd tried to sell his dead wife's clothes to the neighbours, even to Ethel to who he was paying three dollars a week plus room and board. And she told of complaints in the letters

But then I told her of the notations my father had drawn for me in my baby-book describing their marriage as one long honeymoon. After her death he wrote on my third birthday:

I told Ethel of how he'd never removed her picture from the wall till I left home and how he'd put little things of hers away in hidden places to be given to me later. He kept her alive for my brother and me in every way he knew how. Ethel was surprised. He had not yet learned how to share his feelings back then, and she was too young to understand grief and withdrawal nor could she understand the measure of my mother's illness. It was seen as an illness that might have been prevented. She and her family understood it that way.

I asked her what kind of child I had been when my mother died. The pictures taken at the grave each year on the date of her death show me in frills and bonnets, smiling a little, surrounded by baskets of home grown delphiniums or holding a single rose, and my father very thin for the first few years.21b Ethel never appears in pictures that my father takes.

She told me I was withdrawn and quiet, refusing to take part in my third birthday party, a no problem child who did what I was told and didn't fight my presentation as a proper little thing. But I was afraid. As with most three and four year olds who bears chase and lions devour, my fears were exaggerated. The nights were splintered by images of snakes hanging out of dresser drawers. Car trips turned into death hurdles. I feared that the great arms

His anger was directed to-ward his mother Lura. He was losing her too. She had breast cancer and told no-one except her sister, and the Lord.21c Through the remainder of his life my father seldom spoke of her and when he did the underlying anger remained, the outrage that she had not consulted him, her professional son, but chose to place her life in the hands of her Lord who would surely spare her if approached with total faith and supplication, augmented by the efforts of her faith-healing older sister. She died bravely, my father's older brother Clifford said, embracing the surety of a waiting heaven. My father's anger seemed to centre on her, displacing compassion or loss. Perhaps it was his way of cursing his Savior for all of it.