ONTARIO

FARM

DOCTOR WHO BECAME A PIONEER IN MODERN PUBLIC HEALTH

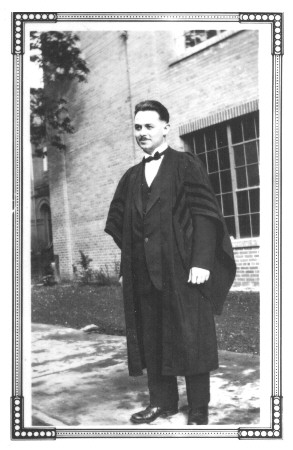

DR. WILFORD E. PARK

Graduation, 1927

University of Toronto

WILFORD EDISON PARK, M. D.

(1901-1985)

This summary was prepared for the memorial service

for Dr. Park held at Hennepin Avenue Methodist Church

in Minneapolis, Minnesota, April 2, 1985.

Dr. Wilford E. Park was born on March 27, 1901 in Fair Ground, Ontario, Canada. He died on February 19, 1985 in Phoenix, Arizona and was buried in Sun City, Arizona.

He is survived by his wife, Dr. Evelyn Hartman Park, of Prescott and Sun City, Arizona; daughter Betty Ponder, of Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada; and sons Douglas Park, of Cupertino, California; Robert Park, of Poynette, Wisconsin; James Park, and Warren Park, both of Minneapolis, Minnesota.

He is also survived by a brother, Rev. Clifford G. Park, of London, Ontario, Canada.

His eleven grandchildren are: Linda Neilson, Jennifer Scott, Kevin Park, Renee Mahan, Donavon Park, Robin Park-Doob, Mischa Park-Doob, Ian Park, Catherine Park, Jonathan Park, and Daniel Park.

His seven great-grandchildren are: Jason Rhinelander, Leta Scott, Michael Scott, Jennifer Park, Carrie Park, Danielle Mahan, and Charise Mahan.

Dr. Park earned his medical degree from the University of Toronto in 1927. He was elected to membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha Honorary Medical Society in 1925.

After being in general practice in Brownsville, Ontario for thirteen years, he moved his family of 6 to Whitby, Ontario in January, 1942 and joined the medical staff at the shell filling plant at Ajax, Ontario. While there he did pioneering work in the prevention of TNT poisoning. From 1945-1949 he was Director of Health Services for the Atomic Energy Project at Chalk River and Hospital Administrator for Deep River, Ontario.

In late 1949, he moved his family (now seven in all) to Minneapolis, Minnesota and became Director of Industrial Health in the Minnesota Department of Health. From 1952 until his retirement in 1972, he served the Minneapolis Health Department first as Chief, Occupational Health Service and later as Director of Adult Health. His duties included protecting workers' health in the workplace and the evaluation and inspection of nursing homes in Minneapolis. He also served as Lecturer in the School of Public Health at the University of Minnesota. He was one of the founders of the Minnesota Academy of Occupational Medicine and Surgery, an organization of physicians specializing in occupational medicine, serving as its first president. In 1973, he moved to Arizona with his wife, Evelyn.

Dr. Park was a member of many professional organizations and served on numerous community organizations on the city, county and state levels in Minnesota. He was listed in Who's Who in the Midwest and Who's Who in the West.

FROM AN ONTARIO FARM

Volume One of the Autobiography of Dr. Wilford E. Park

-- CONTENTS --

| Preface | |||

| Introduction |

| SECTION ONE | CHILDHOOD DAYS AND EARLY MANHOOD |

| Chapter One | FAMILY BACKGROUND AND ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING | 1 | |

| Chapter Two | FATHER REMEMBERS | 11 | |

| Chapter Three | VERY EARLY YEARS | 15 | |

| Chapter Four | LATER PRESCHOOL YEARS | 20 | |

| Chapter Five | ELEMENTARY SCHOOL YEARS | 25 | |

| Chapter Six | HIGH SCHOOL YEARS | 41 | |

| Chapter Seven | THREE YEARS AS A FARMER | 49 |

| SECTION TWO | YEARS OF PREPARATION |

| Chapter Eight | UNIVERSITY YEARS AND INTERNSHIP | 61 | |

| Chapter Nine | YEARS IN GENERAL PRACTICE | 81 |

| SECTION THREE | YEARS OF OCCUPATIONAL MEDICINE IN CANADA |

| Chapter Ten | YEARS IN AJAX AND WHITBY, ONTARIO | 96 | |

| Chapter Eleven | YEARS IN DEEP RIVER AND AT CANADA'S ATOMIC ENERGY PROJECT AT CHALK RIVER, ONTARIO |

114 |

by the author's son

After my father's death in 1985, I assumed responsibility for the publication of his autobiography. From An Ontario Farm is the first of two volumes about Dr. Park's career in medicine. It covers the period from early childhood through his adult professional life in Canada. Volume II of the autobiography, A Modern Public Health Pioneer, covers his professional career as a public health official, first at the Minnesota Department of Health and later at the Minneapolis Public Health Department. His main duties included protection of the individual's health in the work place and health care of the elderly through the maintenance of high standards in the city's nursing homes. Dr. Park's original title for his autobiography as a whole was Autobiography of a Pioneer in the Two Fields of Occupational Medicine and Active Nursing Care. "Active Nursing Care" refers to his approach to caring for the aged in nursing homes.

The reader should be aware that Dr. Park has chosen to write an account of his professional rather than personal life, with the exception of the section about his childhood and youth. Although the writing progresses chronologically, not much reference is made to specific dates. Dr. Park recounts a number of incidents from his life in the form of isolated vignettes, many beginning with "One time..." or "I remember once..." and consisting of only one or two paragraphs. These recollections, taken as a whole, present an interesting and unique capsule of life in the first half of this century.

Dr. Park has separated his account into three general sections:

Childhood and Early Manhood. This includes a colorful description of his childhood growing up on the farm.

Years of Preparation. In this section he paints a picture of life at the University of Toronto in the 1920's, and what life was like for a country doctor in rural Ontario in the 1930's (including the frustrations of the lack of effective medicines and surprisingly primitive treatments).

Years of Occupational Medicine in Canada. This includes his years as chief medical officer, first at a shell filling plant during World War II, then at Canada's first atomic energy project from the last year of the war through the end of 1949.

This memoir represents the chronicle of the achievements of an important pioneer in the field of public health. The background of his early years, college years and time as a country doctor are all preliminary preparation for the major accomplishments of his medical career in protection of worker's health and improvement of nursing home standards in the care of the elderly. Dr. Park believed in the importance of preserving a record of his life and career and hoped that his work might benefit others in the future. His writing is occasionally technical; here he is speaking mainly to his peers in the medical profession. I am pleased to enable this autobiography to reach the public.

| WARREN A. PARK |

INTRODUCTION

These reminiscences are being recorded chiefly for my children, other relatives and everyone else who may be interested.

They necessarily will not document all of the events and influences which have happened during my lifetime. Neither will they contain much information about other members of my family. They will essentially be relatively common experiences of a growing child and a young man in the early years of the twentieth century, followed by some possibly unique developments in adult life.

Chapter One contains an excerpt from my brother Clifford's memoirs. It is

inserted, not only because of its content, but because it will give the readers some

insight into his character and the precision of his diction. He was my closest companion for

many years and his influence is immeasurable.

| W. E. P. |

SECTION ONE

CHILDHOOD DAYS AND EARLY MANHOOD

CHAPTER ONE

FAMILY BACKGROUND AND ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING

Since I was born about one year and seven weeks after the birth of my brother Clifford, we, of course, were very close companions during our childhood days. This means that our environment and experiences in those years were essentially the same.

My brother Clifford, in the year 1980, has written his memoirs under the title, "Eighty Years of Living." So rather than write a duplicate of those years, events and settings, with his permission I am including here, in toto, that portion of his manuscript which is applicable to both of us.

It is appropriate, as he has done, to document our ancestry first. In order to make his write-up understandable, as a part of my background, it is suggested that the reader substitute, in his mind, the word our wherever the word my appears, if appropriate.

"EIGHTY YEARS OF LIVING"

by

REV. CLIFFORD G. PARK

Robert Browning - "How good is man's life, the mere living!"

What a fascinating eighty years of living have been mine! If my life is half as interesting to read about as it has been to live it, this light-hearted sketch will not have been written in vain.

Historians, to be sure, tell us that of the billions of people who have inhabited our planet, only about five thousand have accomplished enough to merit remembrance. I certainly do not belong in that select company, but I hope my career has been interesting and significant enough to make it worthwhile to pass on these memoirs to friends and members of my family.

Genealogy -

To begin with, the Park lineage can be traced as far back as the 6th Century A.D., and we can take modest pride in the fact that a tiny trickle of royal blood, derived from ancient English monarchs, still courses in our veins. This tincture of royalty, however, was derived by marriage from the female side. The direct male ancestry of the Park line is traceable back to Robert Parke of Gestingthorpe, Essex County, England, whose death is recorded in 1400 A.D. The seventh in line - Robert Parke (1580-1665) of Acton County, Suffolk, came to Boston, America on the good ship Arabella, with the Winthrop Fleet in 1630 (acting as Secretary for Governor Winthrop of Connecticut during the voyage.) Robert finally settled in Old Mystic, Connecticut. Many of the Parks of America trace their origin back to him, and in

1

1930 a bronze plaque was erected to his memory in the Old Mystic Cemetery, a cemetery now maintained by the Daughters of the American Revolution. My brother, Dr. Wilford E. Park, and his wife, Dr. Evelyn Hartman Park, visited the cemetery in 1961 and took pictures which he has preserved among his detailed and extensive records of the Park family.

The above Robert Parke married Alice Tompson, a widow with three daughters. One of these daughters, named Dorothy, married Robert Parke's son, Thomas (who was born in Hitchim, England in 1616). Dorothy Tompson had inherited a royal lineage through her mother, and it is from a son Robert, born to Dorothy and Thomas, that our descent is traced and our claim to a royal ancestry is made.

Dorothy's line of regal descent - sometimes through kings and queens, sometimes through blood relatives of reigning monarchs, provides us a background of which we can be justly proud. Her lineage is traceable back through eleven British kings to Cerdic, King of the West Saxons (519-534 A.D.). In her direct line of descent we find Egbert. first king of all England (827-836) and Alfred the Great who reigned 871-901, and of whom an historian has written, "No nobler monarch ever sat upon a throne." Through related lines, it is possible to name 69 kings and queens of England, Scotland and France with whom she possessed some blood relationship. Two examples were Malcolm 1st of Scotland (slayer of Macbeth) and the Emperor Charlemagne. Another was Eleanor of Acquitaine, wife of Louis VII of France and Henry II Plantagenet of England. Eleanor was the mother of two other kings: Richard the Lion-hearted and King John Lochland.

The 1981 - Vol. XVIII, No. 1 News Letter of The Parke Society, Incorporated in Connecticut, documents the ancestry of Diana Princess of Wales, England, back to Dorothy (3) Parke, daughter of Thomas (2) Parke, and his wife, Dorothy Tompson.

Returning to our direct descent from Thomas (2) and Dorothy Tompson, the Park line is as follows:

| Thomas Parke 2 | Dorothy Tompson | |

| Robert Parke 3 | Born 1650 at New London, Conn. | |

| Hezekiah Parke 4 | Born 1695, Preston, Conn. | |

| Silas Parke 5 | Born Preston, Conn. | |

| Amos Park 6 | Born 1749 - becomes the first Canadian. After becoming a physician in Palmyra, N.Y. state, he came to Canada to Niagra-on-the-Lake in Ontario about 1780. | |

| Halsey Park 7 | Born in 1779 in Walpole, Ontario. Died 1848. Buried in Hagersville, Ontario, Canada. | |

| Philip Bender Park | Born in Lyons Creek, Ontario in 1830. Died 1917. Buried at Cultus, Ontario. He became a farmer at Fair Ground in Houghton township, married Margaret Watson (born 1836, died 1915). Had eight children of whom the youngest was Watson. Two daughters and five sons survived to maturity: Agnes, Ezra, John, Michael, Mary, Will and Watson. | |

| Watson Park 9 | Born at Fair Ground, Ontario, Canada on March 12, 1874. Died March 10th, 1956. Buried at Cultus. In 1899 he married Mary Emma Lura Cutler (Nov. 11, 1879-Dec. 31, 1935), the younger daughter of Hugh Edgar Cutler and Mehetabel Edmonds. | |

| Clifford Gordon Park 10 | Born February 5, 1900, in Fair Ground, Ontario. | |

| Wilford Edison Park | Born March 27, 1901 in Fair Ground, Ontario. | |

| Montie Harold Park | Born October 13, 1902 in Fair Ground, Ontario. Died Nov. 18, 1983. Buried at Cultus, Ontario. | |

| Leta Gertrude Park | Born August 8, 1904 in Fair Ground, Ontario. Died January 23, 1978. Buried in Utica, Michigan. |

My Childhood

Weighing in as a "preemie" of 4-1/2 pounds on February 5th, 1900, I doubt if my birth caused much excitement, even in a hamlet as small as Fair Ground. This obscure little village in the center of Houghton township, Norfolk County, incidently, had derived its name from the fact that the township fair grounds were situated on the northwest corner of the intersection, where the annual township Fall Fair was held. Township council meetings were held in its town hall. My actual birthplace (as it was also of my brothers and sister) was the home of my grandfather, Philip Bender Park, who must have early moved to his farm a half-mile south of the main corner- perhaps a century and a quarter ago--to begin the task of establishing domicile in a wooded wilderness.

It was my good fortune to be born of sturdy stock. With a paternal grandfather of English heritage, a paternal grandmother of Irish parentage, a maternal grandfather of Pennsylvania Dutch extraction, and a maternal grandmother whose parents were Scottish (whose own mother, my maternal great grandmother, could still speak a bit of Gaelic and survived into my early childhood), I was nonetheless a trueblue Canadian of the fourth generation, with my roots firmly planted in the soil of this great land where so many blood-streams have intermingled to produce a citizenry worthy to stand beside the best the world provides.

For the first eight years of my life our family lived in the northern half of my grandfather's frame house, located a half-mile south of Fair Ground. Father's elder brother John and his wife Effie and son and daughter Stanley and Vera lived in a more pretentious house on the corner farm just north of us. Stanley and Vera were to be older school mates and play-mates of mine until their removal to Brantford before I was fully grown. But my grandfather's home was a good place to spend one's early childhood. One of my greatest memories is that of looking out my grand- mother's bedroom window watching my father working on the addition which was to make our own family accommodation more adequate. As I think of it now, I realize that our bedrooms were small, but the combined living-dining room in my grandfather's part of the house was very spacious, and the big box stove in the middle of the room had a woodbox behind it which seemed positively huge to a small boy to whom early befell the duty of keeping that woodbox filled. Above this part of the house was a very low attic, a child's haunt of mystery, atrociously hot in summer and inhabited by big black hornets which were, fortunately, too sleepy and apathetic to attack anyone.

3

In his earlier days, my grandfather must have been something of an athlete. He could do a standing broad jump nine feet backwards, and on one notable occasion, he walked the fifty miles from Walpole to Fair Ground in one day, arriving ahead of the stage coach! But he was not only a man of stamina, but a pioneer of vision and resourcefulness. With five strong growing sons to help him, he cleared his land and planned his homestead wisely - building two good barns and a commodious house and planting two acres of orchard with space for a garden. I remember the well-chosen varieties of fruit trees - apple trees, which included astrachans, talman sweets, russets, greenings, kings and northern spies. And there were other fruits as well: sour red cherries, small blue plums and small peaches - all a tasty treat then, but a far cry from the big luscious varieties we know today. In season also, the garden produced black and red currants, strawberries, red and black raspberries and long black thimbleberries. I can see the thimbleberry patch yet - down beside the outdoor privy, beyond the little smoke house where hams and bacon sides were cured, and the old fire-place where my grandmother made soft soap from fats and the lye she leached from ashes. Nearer the house stood the outside cellar, the soft water cistern and the well at the back door, from which water always pure and cold could be enjoyed by anyone energetic enough to operate the pump handle. And never far away was the woodpile and its axe from which wood for the kitchen cook stove or the living room box-stove could be secured as required. Out front on the roadside stood two huge balm-of-gilead trees, redolent with the healthy odour that distinguishes their species. Across the road the little creek wound its way through a neighbour's swamp, down to the old swimming hole which we boys had created by damming up the creek, and in which we learned to swim the dog-paddle without instruction. From that swamp on warm summer evenings, the frogs would lift their voices to rival the birds in a chorus of nature that was always music to our ears.

In spite of the usual childhood diseases, we had a healthy and certainly a happy childhood. I remember how ecstatic I was as a tiny lad on Christmas morning to find that Santa Claus had left a handful of nuts and hard candies in my stocking, an orange, a top, and a whistle, as my share of his Christmas largess. We children were up early before the wood stove was alight, and our bare feet chilled on the linoleum floor - but that in no way detracted from the thrill of our Christmas morning, nor dulled our parent's delight in our happiness. I never had any sense of economic deprivation as a child.

Indeed I shall never feel so economically well-to-do as I did as a little lad of six or seven, when my father brought home to live with us an English girl from the Barnardo (?) Homes. They arrived after the usual evening meal, and mother gave her bread and milk for supper. I remember how my heart swelled with pride as I reflected how wonderful it must be to enjoy our plentiful and delicious bread and milk after the Sparten diet I assumed she had had to endure at the Home. (I still like bread and milk, especially if I am a bit under the weather.)

Actually we were not quite as well-to-do as I assumed. My grandmother found it necessary to dry apples each winter on a big screen over the kitchen stove to earn some extra cash for the store. How else could she have secured the sugar and flour for the delectable cookies which established her as a small boy's favourite grandma? President Roosevelt in one of his fireside chats, declared that "the people of America were one-third ill-housed, ill-clothed, and ill-fed." Some wag commented that "this country was founded by people who were ill-housed, ill-clad and ill-fed, and didn't know it!" To a considerable degree that applied to us, even though we ranked as one of the more affluent families. With our poorly insulated wooden houses,

4

our wood stoves and coal oil lamps, lacking both a basement and inside plumbing, we were by today's standards, ill-housed. And we had little to spend on clothes. Even at 19 years of age when I started to Albert College to train for the Christian ministry, I had only one suit and its sleeves had already started to fray and my mother had to turn in the edges of the cuffs to hide the worn spots. But we were never ill-fed, for we were active farmers producing the bulk of our own food in our own fields and gardens. For many years my father grew six or eight acres of potatoes a year - (How skillful I became in hoeing out the weeds and picking off the potato bugs with pail and paddle!) We butchered our own hogs and milked our own cows, sending the milk to the local cheese factory, shepherded our own sheep, had enough chickens and hens to keep us in eggs, and some geese and turkeys to provide a special treat for Christmas and Thanksgiving. In winter we felt no hardship to breakfast regularly on buckwheat pancakes along with fried ham or bacon, and maple syrup to top off the final helping.

Besides, food prices were unbelievably low. In 1908 the Cutlers moved to a new cement block house a stone's throw west, beside the little white Methodist Church, and my father and mother took over from them the rambling old country hotel which stood on the south-west corner of the intersection in order to board the workmen employed at the new sawmill which had been erected a quarter mile east on my uncle John's property. During that period, one butcher offered Dad all the hind-quarter beef he could use at a standard price of eight cents a pound!

But I count it part of my good fortune to have been born and reared on the farm. Not that I do not recall some anxious moments from my early childhood. For instance, there was that time I waded across the neighbouring creek when it was swollen with the melting snows of Springtime, and promptly came down with a bad case of croup. A neighbouring woman (Mrs. Mel Williams) came to sit out the night with me and administer hourly a concoction which didn't taste bad at all - anyway, I was better the next morning. Only years later did I learn the medicine was a mixture of honey and urine! At least it was harmless, but I won't try to recommend it for anyone suffering from croup today.

And then there was that day Wilford and I undertook to kill a turtle not much bigger than a watch. We found it in the creek and had heard mother say its shell would make a nice ornament, so we decided to cut its head off. After argument, I conceded Wilford the privilege of wielding the axe and he cut off the end of the first finger of my left hand! It didn't hurt much, but it bled profusely, and I pictured myself bleeding to death. I let out a yell that must have been audible a half a mile away. Just then mother was sitting on the throne in the old three-holer beyond the smokehouse. I ran to show her my bleeding hand, but wisely she tried to calm me and emerged to bandage the finger as quickly as she could. I am sure that was one day mother needed no prune juice or epsom salts! Care and Zam-buck ointment healed the wound but that first finger has always been a little shorter than its mate on the other hand.

Of course there were amusing moments too, and Dad seemed to have more than his share of them. But one that tickled us most had to do with his regular Saturday night bath. We were accustomed to heat the bath water in big kettles on the kitchen stove and pour it into the big tin tub Dad had made with a wooden

5

frame for our weekly ablutions. However, we were accustomed to tap the maple trees around the house each Spring and boil down the sap into syrup in the big pots on the stove. This particular night Dad mistook the partially boiled sap for his bath-water and used it for his bath - quite the sweetest bath he ever took, I am sure, and probably unrivaled in anyone else's experience. But maybe not an unfitting external accompaniment for the inner good nature that was so conspicuously his!

It was from the home south of Fair Ground that I started to school at six years of age. I didn't like it and came home at the first recess saying I wasn't going to go. Of course I had to go back, but I remember lying awake one night wishing for the time I would be done with school. Little did I realize then how much I would learn to love school; nor did I dream it would be twenty-one years later that I would finally graduate from theological college and be done with the class room forever.

I did not have to be long at school before I learned to enjoy reading. Having devoured the Henry and Horatio Alger books on our own shelves by ten or eleven years of age, I cast about for something of deeper interest and found it in a book in Aunt Effie's library. It was Robinson Crusoe, and the book proved so fascinating that I stole over to read it for hours at a time without telling anyone at home where I was going. This latter indiscretion led to the only real spanking I can remember my father ever giving me, and punishment did nothing to warp my ego or dampen my enthusiasm for reading, but it did teach me to be more considerate of my responsibility to others.

During the four years Dad and Mother operated the boarding house for about twenty millworkers - until the mill characteristically burned down when the available timber was exhausted - they continued their regular farming and nearly worked them selves to death trying to carry two jobs at once. Meanwhile, I continued to attend the local public school a quarter mile north of our house, and did what I could to help on the farm.

I had done rather well at public school and at twelve years of age I had passed my High School entrance exams - rather young, but then I had a father who had done it all at eleven years of age, and had come first of the twenty-six township students who had written their entrance exams.

But now with the mill gone and the boarders gone as well, and Dad able to give full time to his farming (plus some extra time spent barbering on Saturday nights, and his not too exacting responsibilities as Clerk of the Seventh Division Court of Houghton township), I could be more readily spared. So September 1912 saw me a student in the high school at Vienna, a village eight miles west of Fair Ground. Vienna high school had only about thirty pupils, but excellent teachers, and in three years I had finished high school with what was called a Normal School Entrance Certificate (one language short of matriculation). The high school arrangement had been for me to board in Vienna from Monday noon to Friday noon and return home each weekend. Incredible as it seems now, I was able to get the four nights' accomodation and thirteen meals a week for $2.00 per week, and if I remember correctly, I was paying only $2.50 a week when I finished high school In June, 1915. Inflation was not a significant problem then.

Now it was Wilford's turn to go to Vienna to high school, and when he finished, Montie's turn, then Leta's. So, it turned out that from 1915 to 1918 I was at home again, giving now all my time to working with Dad on the farm. At fifteen I was too young to enlist, and anyway, as a farm boy, I was excused from military service

6

because engagement in agriculture and food production was deemed an essential part of the war effort. In that rural setting, with radio not yet invented, without a daily newspaper, and as far as I know, none of my schoolmates in the Armed Forces, the War did not seem to touch our lives very closely. But I do vividly remember the joy of that memorable November 11th, 1918 when the whistles began to blow to announce that the Armistice had been signed and the war was over. That afternoon my father and I were shingling a new shed in our shirt sleeves, and I doubt if we have had as warm a November 11th since.

My formal education was soon to begin again, but I have never regretted the three and half year interlude in my academic career. I was at home at a time when I was sorely needed. We lived in the corner house but farmed two farms of our own, one a half-mile south and the other a half-mile west, and worked and rented land as well. Our farming was done the hard way, by hand, or by primitive horse-drawn machinery. I had as yet hardly seen a tractor or a milking machine. Corn binders and hay bailers were still a foreign curiosity belonging only to more affluent farmers, and an automobile was still out of the question. We took the cows and the horses (eight of them) down the road to pasture at night, and it was fun to ride one of the horses bare-back, set the dog on the other seven, and go down the road like a charge of cavalry. No wonder pedestrians leaped out of the way as we passed, and I am afraid the look on their faces often betrayed an emotion other than fear. But after getting tossed off on my head by the horse, I was less prepared to ride without bridle.

By chance, around Christmas, 1917, after I had finished school and Wilford was now attending High School in Vienna, Montie upset a lantern in the straw mow and the whole barn went up in flames. He was lucky to escape from the blazing inferno, and neighbours helped drive the cattle from the shed and lead the horses from their stalls so that only a sow and a colt died in the blaze. I happened to be away and was sorry to have missed the excitement, traumatic though the loss seemed at the moment. But luckily Dad had already contemplated building a new barn and it was now only necessary to hasten the project. Already Dad and I had spent two winters cutting off the seven acres of virgin bush at the rear of the west 50, bringing home the long straight timbers to be shaped into beams for the new barn, and cutting the others into logs to be taken to the mill to be sawn into lumber for sheeting and siding. Chain saws were not yet in use, and it brought my father and me very close together spending those two winters on the opposite ends of a cross-cut saw.

The third winter (1917-1918) 1 spent in Brantford working at Adams Wagon factory, and boarding with Aunt Effie, Stanley and Vera (Uncle John having died of cancer in 1916). They moved to Brantford a few years before where Stanley was a motor mechanic and Vera a school teacher.

In the Spring of 1918, 1 returned home to do the farming while Dad and an experienced carpenter worked on preparing the timbers for the barn, shaping them with a broad-axe, and mortising the ends for the raising. The raising was a big event. Neighbours gathered for miles around to lend a hand with ropes and pike-poles and their own strong backs. I was proud to have a part in it. When the frame was in place, I helped with the sheeting and shingling and painting. But never unwilling to engage in a harmless prank, I caught the neighbour's rooster who was too ardently visiting our hens without an invitation, and I painted him a brilliant red from comb to tail. Understandably, the neighbour wasn't too pleased to see his rooster so brilliantly bedecked. He complained, "The hens didn't know him!"

7

And lest readers might assume I never engaged in any other mischief, I will confess that one Halloween night, after Wilford and I had gone dutifully upstairs to bed, we climbed out our bedroom window, unbeknown to Dad and cut the chain securing a neighbour's gate - which he boasted was prank-proof, and deposited the gate in his own haymow where he found it not too long after. When someone discussed the disappearance of the gate next day, Dad remarked that his boys were innocently in bed. The other said: "Don't be too sure!", but happily nobody pressed the matter any further.

However, the legacy of my years on the farm were both great and positive. My character, my habits, and my outlook on life were shaped and matured by these years in the great outdoors. I learned to enjoy Nature, and feel at home with Nature's God. The fields, the trees, and growing things, the animals, the sun and the rain, and the open sky, the stars and the glory of the sunset made me look beyond the things that are seen to the wisdom and love of their Mighty Maker. As a farmer, dealing every day with the forces at work in our world, I was an existentialist before I had ever heard that word for Sartre's now popular philosophy. But I was a religious existentialist, convinced that behind the seen and heard, and the known, stands invisibly a wise creator and a loving God. Perhaps that is why I have always loved the hymn:

This is my Father's world, And to my listening ears All nature sings And round me rings The music of the spheres. In the rustling grass I hear him pass: He speaks to me everywhere.

I learned too, from years on the farm, that work comes before play, and I think I would have agreed with F. R. Barry who told the students of St. Andrew's University in his rectorial address - "There may be something that is more fun than hard work, but I do not know what it is." Anyway, I had plenty of it. One summer I got up at a quarter to five each morning to fetch the cows and horses from pasture, get the feeding and the milking done, and after a gargantuan breakfast, be ready for the day's work in the fields. The ability to work hard and consistently and do it happily, has stayed with me all my life, and doubtless has been a major secret of my success in life.

FAMILY BACKGROUND AND ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING (CONTINUED)

Now that you have read Clifford's description of our childhood environment, I want to add a few small details which he left out.

The little creek, which Clifford mentions in the swamp across the road, emerged from Uncle John's farm, where it adjoined grandfather's farm, at the road. The creek there crossed the road and flowed in a south-westerly direction into the adjoining farm on the south side of the swamp. It was under the bridge across this creek, on the road, where we found the small turtles mentioned by Clifford, in about two inches of water.

Clifford's reference to our swimming hole, in the creek across the road, brings to mind our improvised water wings, consisting of a couple of pieces of small logs extracted from our woodpile. Across these we had nailed a leather strap. To swim

8

we lay in the water with the strap across and under our chests. The floating wood held us up and we were free to flail with our arms in learning to swim.

The swamp across the road from grandfather's house used to have beautiful blue flowers in it, which we called flags. In later summer evenings, all over this swamp there were glittering flashes of light which we found came from fireflies. We caught some of these flying insects, and even in captivity, they would periodically cause their abdomens to glow momentarily. We experimented by crushing some of them, and we found that their tissues, when crushed and spread out, continued to glow for a time in the dark.

The ditch beside the road next to grandfather's fence grew lots of cattails. When dry, we sometimes cut some of them and dipped them in coal oil (kerosene), then lit them and paraded with the torches at night.

From the road grandfather's home property was entered through a small gate. There was a front door in the house which was seldom used, that opened immediately into the living room (which also served as the dining room). Most traffic was through the door on the south side of the house, which opened into the kitchen. Between the kitchen and the living room was a narrow pantry that took up most of the space.

Clifford has mentioned most of the buildings on the property. Behind the residential area was the barnyard, which was quite large, with a fence around it, enclosing the farm buildings. On the south of the residential property, the barnyard was connected with the road by a wide lane, with a gate at the road. Farm animals had access to this lane. This lane also contained the piles of wood used to heat the house. Some of the fruit trees, mentioned by Clifford, were on the north side behind the house and some were on the south side of the lane. Most of the garden was also on the south side of this lane.

There were a few more fruit trees which Clifford did not mention. There was a crabapple tree which supplied small apples for jelly. There was also a fall apple which was dark red in color which we called wine apples because of the color. I remember too a small, very sweet pear which was russet in color. It may have been an ancestor, or relative, of the Bosc pear. Winternellis pear appears to be identical. Every year some of the apples were taken to the cider mill where they were crushed and the apple juice brought back in barrels. Some of this cider eventually became cider vinegar.

In front of grandfather's residence was a lawn of sorts, bordered on the north by lilac trees. There was no lawn mower so the grass was kept under control with a scythe. At one point over the fence, at the road, was an elevated platform called the milkstand. On it every morning the milk cans were placed, where they were picked up by the driver of a horse-drawn wagon with a flat top, and taken along with other supplies of milk to the local cheese factory. The milk cans were later returned to the milk-stand with some whey in them, which was used for pig feed.

Grandfather's barnyard was connected with the fields on the farm by a lane which was entered through a gate on the south side of the barnyard. This lane for some distance ran along the eastern border of the garden toward the south. Later the lane turned to the east and ran all the way to the eastern limits of the farm, giving access to each field on either side. The gates to each field were kept closed

9

except for the fields used for pasturing animals. The cows when admitted into the lane at the barnyard end, found their own way to pasture, and returned by themselves to be milked, every evening. One feature about the farm in those early days was that all of the fences were either stump fences or zigzag rail fences.

I recall one time, when we were in the attic of grandfather's house, we became curious about two smooth pieces of narrow wood which were attached to the rafters with one end of each bent in a curve. Much later these pieces of wood turned up as the runners of a sleigh which Dad built for us.

Clifford in his comments on the burning down of our barn referred to the loss of a sow and a colt. On the next weekend, when I was home from school, Dad told me of seeing the sow run out of the burning barn with the grease bubbling out of her back like bacon in a frying pan. He said she was so desperate with pain that she turned around and ran back into the fire. Later in my diary I found that the date of the fire was December 18, 1917.

Later I learned that Dad had no fire insurance on the barn, but he said his neighboring farmers and friends got together a purse containing $700.00 and gave it to him.

I remember when the new barn was being built that Dad consulted us boys about a name for the barn. We suggested Golden Glow and it bore that name on its western side as long as it was standing thereafter.

10

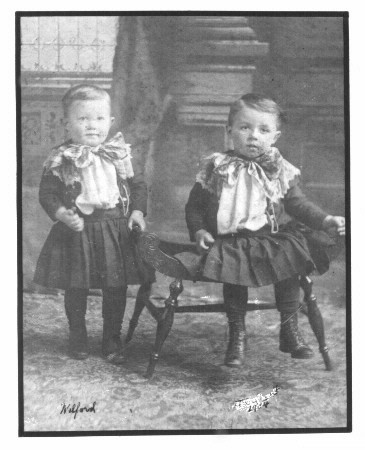

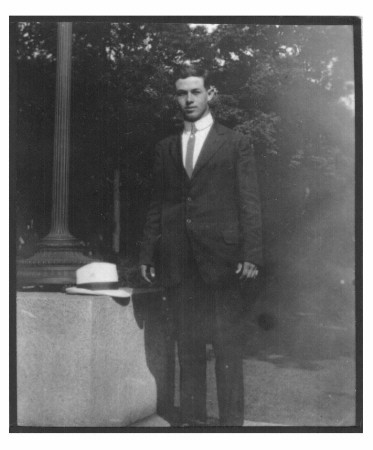

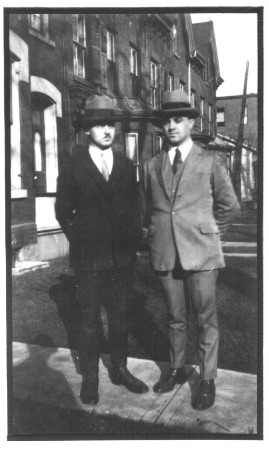

Wilford Park (left) and Clifford Park (right)

photo taken in 1904

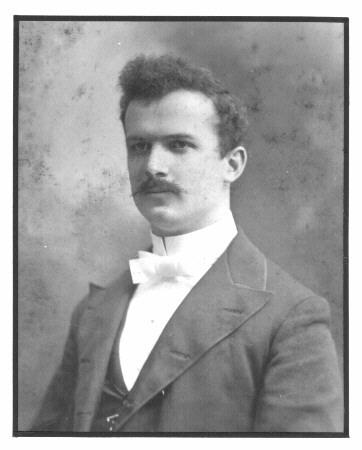

WATSON PARK

(1874-1956)

at about 21 years of age

(father of Clifford, Wilford,

Montie and Leta Park)

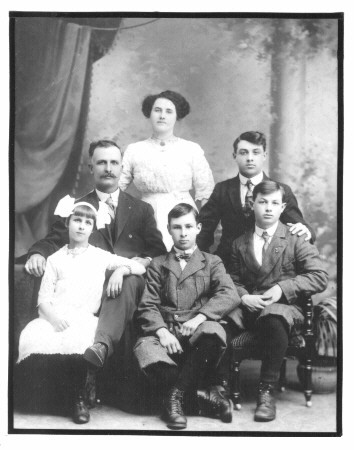

(back row:) Watson, Lura, Clifford

(front row:) Leta, Montie, Wilford

(note from Clifford:)

"Clifford was home on the farm at

the time the picture was taken.

The color and weariness in his eyes show how hard he had been working!"

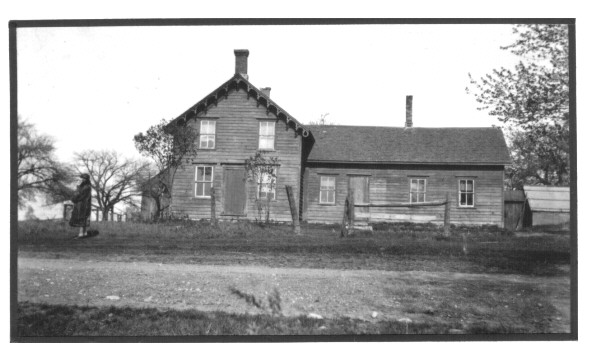

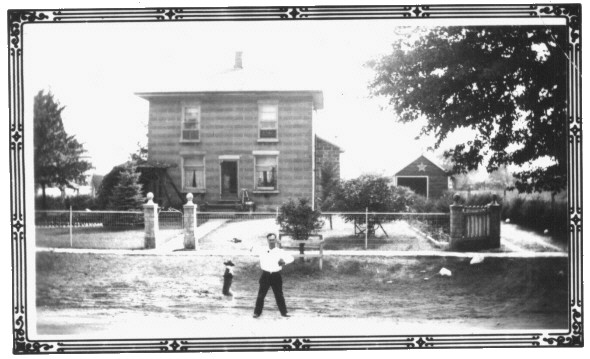

Fair Ground, Ontario

Home of Philip Bender Park

Birthplace of the family

of Watson and Lura Park

(Clifford, Wilford, Montie and Leta)

CHAPTER TWO

FATHER REMEMBERS

It seems appropriate, at this stage, to record some family events which took place before I was born, and which were told to us by my father, Watson Park. These stories are memorable sagas, carried over from my boyhood days. No attempt will be made to record them in chronological order nor to relate them to each other,

My father was born in a shanty in one of the backward townships in Ontario, Canada. He didn't remember much about the shanty, but he was told that it served for a home for about seven years, while a house was being built to replace the one which was burned down.

My father was the youngest of the family of eight. Two circumstances stood out in his early childhood. One was when they carried his six-year old sister Auzuba away in a white casket, bearing waving plumes of white ostrich feathers. She had died of diptheria. The other event happened when he was three years old. One morning at mealtime he found himself looking at two rounded objects, each covered by a dreadful black ring, where his breakfast had always come from. With a sinking heart he turned away forever and thereafter he had to get his milk from a cup. Years afterward he learned that he had been nursed unduly long to minimize the chance of another pregnancy. He was then told that the black rings had been ink applied by his mother.

One evening my father went with his parents, Philip Bender Park and Margaret Park, to call on one of the neighbors, who had a reputation for being dirty. When they arrived they found the untidy woman of the house, lying in bed with the one-time white sheet pulled up, so that her bare feet were sticking out in the warm air. Between her toes were dried remnants of cow manure and mud from the barnyard. The wall beside the bed was covered with stains of tobacco juice, because the old lady liked to chew it in bed. She jumped out of bed, happy as a lark. She was so glad to see her friends that she sat down, in her night gown at the old organ, and played and sang for an hour. She could really sing and play too, although she couldn't read a note of music.

Boyhood days, for father, centered around the farm, the school and the church. The old frame schoolhouse was not too tightly constructed, and the Schoolmaster's eyesight was not good either. So sometimes a boy got away with the use of a knot hole, instead of going outside to the special building set aside for toilet purposes.

Father attended public school with his brother William, who was one year older. Father and his brother William tried the entrance examinations together, along with twenty-four others in the township. The two of them came out the best in the group, with my father getting the highest marks.

My father had a remarkable memory. When he wrote the examination in history, he wrote down word for word what the condensed history book contained, and the examiner certified that it wasn't copied from the book, because he stood over him and watched him do it, much to his own amazement.

11

My father's brother William went on to high school and became a public school teacher, and earned a salary of $350.00 a year, on which he lived and raised a family.

My father did not get any advanced education except a little high school work taken in Public School.

Father remembered another occasion when he demonstrated his remarkable memory. In Sunday School the pupils were engaged in a competition to see who could learn and recite the greatest number of bible verses. This competition father easily won, by reciting from memory the whole of the gospel of St. John.

When father was a baby, he had a couple of bad experiences, which of course he didn't remember, but he recalled having been told about them. His parents told him that, when he was a baby, he occasionally had fits, and got blue in the face. One day when he had one of these spells, his sister Mary picked him up from his crib and ran outside with him. In passing through the door she struck his head on the side of the door and nearly killed him. On another occasion my father was rescued from the white-faced mare which had found him out of doors lying in his crib. She had picked him up in her teeth, with a grip on the clothing in the middle of the stomach, and was swinging him back and forth.

One day father recalled that a stranger came to see my grandfather. He found my father and his brother William, as boys, standing together. He said, "Where is your father?" Father's brother Will promptly said, "He is in the backhouse." How well I remember that ancient building. Even in my day it was quite stable with accommodations for four people at once. At the sides between the upright studs were pockets for old newspapers, because toilet paper was unheard of when I was a child. There was a special compartment close to the end hole, which my grandfather always used. This compartment my grandfather used as a spittoon while he sat on the toilet chewing tobacco. I remember this compartment had a layer of dark-brown coating on it one half inch thick.

In my father's family the boys had to help do the farm work early in life. One day father and one of his brothers were driving a pair of yoked steers which were pulling a stoneboat, on which they were riding. It was early spring, with some snow still on the ground, in patches. They were unable to control the steers and they ran the stoneboat under a large stump, which was propped up by a rail. The stone- boat, with my father still on it, came up short against the rail. Fortunately the rail held in the frozen ground or the stump would have fallen and crushed him.

One time grandfather sent one of the boys to the cider mill with a load of apples. The boy drove along the strange road until he approached a jog in the road. He could see the fence across the road, in front of him, so without going farther he turned around and came back home and announced that he could not go any farther, because he came to the end of the road. Grandfather was so angry that he turned the team around and whipped the horses to a run as he tore off for the cider mill himself.

One day two of my father's brothers, when they were still boys, drove a team of horses with a wagonload of grain to the gristmill. When they reached the millpond they realized that the horses were thirsty, so they drove them to the edge of the millpond to drink. The heavy load, on the downgrade, kept pushing the horses deeper

12

into the water. Soon the horses were struggling in deep water with the heavy wagon pulling them under. The boys scrambled to shore but the horses were drowned in the millpond.

Grandfather and grandmother were faithful supporters of the little Methodist Church which was located on the corner of grandfather's farm. Grandfather for many years was class-leader in that church. Father said the congregation could not afford a janitor, so his mother cleaned the church for nothing. Many a time he said he had seen her on her hands and knees scrubbing the tobacco-juice stains off the old wooden floor. The church building was eventually moved to a new location. One of the neighbors was so angry about it that she wouldn't attend that church again.

There was one old white-haired man who was called Daddy White. He used to attend the Methodist Church and when he felt blessed by the service, he would come out of the church saying, "I'm in the ark! I'm in the ark!" One day one of the old jokesters of the day put his hand on my father's head, when he was a child, and said, "Here's old Daddy White." Father remembered that he was so alarmed he hurried home to look in the mirror to see if his hair had really turned white, like the old man's.

My father recalled that, like all boys, his eyes were bigger than his stomach. One day, when he was visiting a neighbor's for dinner, he filled his plate full of potatoes, and kept his eye on another huge one in the serving dish. He thought to himself, I'll have that one next. Without realizing it, soon he reached over and speared the big potato on his fork. When he held the prize in the air, to his horror, he looked down at his plate and found it was already so full he had no place to put it.

When father was a boy, there was a quaint character called Jim Dad Moore, who was always hard up and seldom went into the village, unless he walked. He would never come out and say "yes" when asked if he wanted something. He always answered, "I don't care if I do." One day my father was driving a team on a wagon, and overtook Jim Dad Moore walking along. Father said to him, "Do you want a ride?" Jim Dad Moore answered, "I don't care if I do." Father stepped up the horses and said, "Well if you don't care I don't either" and left the old man plodding along. After another half-mile farther father stopped the team and asked again, "Do you want a ride?" He got the same reply, "I don't care if I do." So my father said, "I don't care either" and away he went again, without giving him a ride.

Old Jim Dad Moore was a lonely man who lived alone and cooked for himself. One day, when he was having dinner with father's brother John and his wife, they offered him the supply of soup for the four of them, for him to have first helping. Jim Dad set the dish down in front of him and ate it all.

One hot day in school, my father remembered the time when one of his school mates was punished by having his hands tied together under his bent knees, and told to sit on a bench in the corner while the class continued in session. After a while the boy went to sleep in this precarious position, and fell forward and struck his head on the floor and yelled to high heaven in the middle of the class.

One time my father said he and his brother were riding with the Francis boys to church at Cultus, in their democrat wagon. There was only one seat at the time so the Park boys had to stand up and hang onto the back of the seat in front of them. For sport they made the horses run, while the boys in unison threw their weight

13

alternately from one side to the other. This caused the democrat to sway violently so that, at that speed, they threw the sand first to one side and then to the other all the way to the fences.

One day my father said he was riding home on the back of a placid and uncomplaining cow. As he passed through the village of Fair Ground and was riding by his brother John's house, his nephew, Stanley, slyly said to his dog, "Sic him Caesar." The dog slipped up behind the cow and nipped her on a leg. The cow made a sudden leap forward and my father toppled off backwards onto the ground, much to the amusement of Stanley. Fortunately my father was not hurt but he was indeed surprised and embarrassed.

On another occasion my father was riding home over the same route on the bare-back of a horse. It was twilight, after a heavy rain, and the creek close to home was in flood but not running over the plank bridge. The bridge was reasonably wide but there was no railing or barrier of any kind on either side of the bridge. During the storm the wind had blown a piece of white paper onto the bridge, where it was stuck on the wet planks on the east side of the bridge. The horse, wild-eyed at sight of the paper, began to move sideways away from it, at the same time keeping an eye on it. When my father saw what was going to happen, he slid off the horse just as the horse fell sideways off the west end of the bridge into five feet of water. The horse fell on its side and became completely submerged. The horse scrambled out without help and walked on home, very much humbled and embarrassed.

Map of Fairground

14

CHAPTER THREE

VERY EARLY YEARS

This chapter contains some incidents which took place when I was still a very young child, and were omitted by Clifford in his write-up of those times during which we were very much together.

I was born on March 27, 1901 in my grandmother Park's house. What was most significant to her was that I was born on her birthday. On this date she was 65 years of age, so I have no recollection of my grandmother as being anything but an old woman.

Since I was born on her birthday, grandma was invited to give me a name. She chose to name me after Thomas Alva Edison who was, at that time, becoming famous as an inventor. She gave me the name Edison but my parents didn't like it well enough to use it as my first name. Rather they called me Wilford, being careful to spell it that way to make it closer to the spelling of Clifford, and at the same time definitely not like Sir Wilfrid Laurier who was Premier of Canada at that time, and a leader of the liberal element in politics, whereas my father was a staunch conservative.

My grandmother, however, would never call me Wilford, but always addressed me as Edison. She always pronounced it with a long "e" and I never learned what was the correct pronunciation until I entered high school. Under the circumstances it is not surprising that I was her favorite grandchild.

One of my earliest memories is of tin pans of milk standing in the pantry in grandmother's house. After standing overnight there was thick cream on the top which was skimmed off with a large tin scoop with holes in it, through which the milk would run but the cream would not. Of course there was no mechanical cream separator in grandma's household and this was the only way to collect cream for churning. When enough cream was collected to make butter it was churned in a churn with a dasher which was operated up and down by hand. Since there was no refrigeration in grandmother's day the butter was always made from sour cream. Many a time I have sat and watched her squeezing the buttermilk out of the clotted butter, in a large wooden bowl with a wooden paddle and after salting it, forming it into large rolls of butter.

My grandmother had a treadle-operated sewing machine, which I spent many pleasant hours playing with. The foot-plate was of metal with small holes in it which was large enough to accommodate both feet of an adult operator. The foot-plate was mounted on an axle in its middle. It provided power by the operator alternately tipping the feet so that pressure on the ball of the feet followed by pressure on the heels kept the foot plate moving. A wooden shaft from the edge of the foot-plate passed to a short crank on the side of a large fly-wheel which would spin beautifully while I pumped the pedal. Of course nothing happened to the sewing machine mechanism because, all of the time I had anything to do with it, the sewing machine head was packed away in its recess, and the round leather belt from it to the fly-wheel was so slack that no power was transmitted to it.

15

Another mechanical hand-operated machine in grandma's house which intrigued me was a machine for peeling apples. It was attached near the end of a narrow board upon which the operator sat to hold it steady. The operator turned a small crank with the right hand, which was attached to a circular cogwheel with the cogs on its circumference on the side of the wheel away from the crank. The axle of the cog-wheel extended to the left where it terminated in a four pronged instrument on which the apple was spitted at its stem end, when the machine's peeler was automatically positioned well out of the way. The peeler consisted of a sharp knife fixed on the end of a curved spring-pressured shaft which, when the crank was turned and the apple spinning, came down slowly onto the blossom end of the apple and moved slowly over the spinning apple until it had covered the whole surface and lifted off again, at the stem end of the apple. The knife was attached to the shaft with a guard on the end so that a slot about 3/4 of an inch wide was created. During the peeling of each apple a continuous strip of apple peeling came through the slot so that the collecting pail beneath the machine contained many strips of apple peelings about three feet long. What fun I had with those long strips of apple peeling, sometimes even eating them without their breaking.

Grandma had a high-backed rocking chair which she kept near the wood-fueled cooking-range in the kitchen. One day I was standing up in her rocking chair, with my back to the stove, having a glorious time rocking briskly in the rocking chair, while hanging onto the back of the chair to maintain my standing position. Suddenly I rocked so hard that I went over backwards taking the rocker with me. Of course the back of my head struck the iron edge of the stove and cut a wound about 3/4 of an inch long all the way through my scalp. It bled profusely and I still carry the scar on the back of my head.

In grandma's large living room over the large dining table, in the center of the room, was a beautiful lamp which hung from the ceiling. It had a large porcelain shade on it which was decorated in interesting flower-like colors. It also had a metallic perforated gold-colored rim which helped to support the porcelain lamp shade. The lamp was suspended by a counter-weighted contraption which allowed the lamp to be raised or lowered by simply pulling it down or pushing it up. It was so well balanced that it would stay in any position one wished to put it. It was, of course, a kerosene lamp, but it was both beautiful and efficient and a marvel to a small child.

In grandfather's house near the head of the narrow stairway in the attic was a small mysterious room which had no light in it. It was frightening to me because it was so dark in there, and hanging from the ceiling was a collection of smoked and sugar-cured hams. It served well its intended purpose but to me it was a place to be avoided.

Grandma Park was very religious. She read scarcely anything except her bible, and her songs were always hymns. She liked to sing and I learned to like many of the hymns she sang. She had a favorite farewell goodbye message which she frequently used when leaving friends or relatives. It was the words, "Meet me in heaven". Obviously she believed in the life hereafter and expected to meet and know people there.

Many of my early childhood memories are associated with grandfather's farm animals. I remember so well the strutting gobbler, with his beautiful tail unfurled and showing off for his adoring females. I was impressed with the size of the goose

16

eggs, so clean and white, much larger than hen's eggs and longer in shape. The turkey eggs looked huge to me, with their brown spots on them.

I was somewhat afraid of the flock's gander. He like to hiss at me and chase me, although he never actually attacked me.

Grandfather's flock of sheep were mild mannered and tolerant of us children. The ram, however, although not vicious, used to take pleasure in pushing me over and doing it again whenever I stood around among them.

I remember one time Clifford and I had a luxurious time lying in the warm straw in the sow's pen under the barn. When we eventually tired of it and went into the house and told mother about it, she was horrified and immediately set about ridding us of the fleas we had collected.

I remember the time mother had quite a time with all of us sick at once with scarlet fever. Fortunately we all recovered with no serious effects. While on the subject of illness I should mention mother's favorite medicine for anything. It was a tiny vial of a black concoction called medicumentum. She always served a few drops to us on a spoonful of sugar. I do not recall that it ever did us any good nor did it ever do us any harm.

I remember that when a small child Clifford and I were always around together. Some of our friends thought I was slow in learning to talk. The trouble was not that I couldn't talk but that I didn't need to. Whenever there was any communication with anybody Clifford was always ready to give all the answers and I got along very well without having to say anything.

Our mother was an expert seamstress and made all of our clothes for us. One time she dressed both Clifford and me in little suits with plaid skirts and took us to Tillsonburg where we were photographed by a professional. I still have a copy of that picture. It really is a nice picture but I am obviously too fat in it. I don't know why our mother wanted to dress us in skirts but maybe she secretly, at that time, was hoping for a daughter or perhaps she had a desire to see her boys in kilts because of her Scottish ancestry.

I remember one hot summer day Clifford and I were on our way to grandfather Cutler's house on the corner in Fair Ground. That day we were strolling along with nothing on but our short pants, held up by suspenders, which we called braces. I got too hot so I took my pants off and carried them by the braces over my shoulder. When we were about to pass Sol Smith's place a couple of doors from grandpa Cut ler's house, he stopped us and jollied me about walking without my pants on. It was Sol's custom to call us Pat and Mike. Pat meant Clifford and I was Mike. He treated us like two inseparable Irishmen. Maybe he wasn't so far off at that, because our grandmother Park was Irish.

The general store in Fair Ground, in those early days, was operated by W. B. Gates. He and his family lived next door on the south side, in a fine house. My earliest remembrance of being in the store was associated with the presence of the Gates' huge black Newfoundland dog. He strolled harmlessly about the store dragging his long toenails on the wooden floor at every step.

17

Right next to the general store on the side next to grandpa Cutler's property was a small shop where Mr. Lindsay, Mrs. Gate's father, made shoes and boots. They were all custom made from a piece of leather. It was a fascinating shop to a small boy.

I remember one time, in the winter after a snow storm, Clifford and I were proposing to walk up to grandpa Cutler's. My father discouraged us because he said he didn't think the road was broke. I didn't know what he meant, but I pictured a dangerous crack in the road which we might fall into.

I remember one Sunday grandma Park was dressed to go visiting and she appeared on the lawn, in front of her house, wearing a huge hooped skirt. I think it was the first time I had ever seen a hooped skirt. It reached all the way to the ground and I could not even see her feet.

One time I recall ~ found myself looking anxiously through grandfather's fence at the road where a huge puffing steam engine was passing by, hauling a threshing machine. The engine was one of those early models which had a huge funnel-shaped Smoke-stack never seen in later models.

One of the scary things I remember is looking down into grandfather's cistern for the first time. This was once when he had the cover off. That big tank of black water down in the concrete hole frightened me.

One time Clifford and I climbed on top of the fence behind grandpa's root and fruit cellar, which was a low building with the room built down into the ground. From the fence we were able to crawl through a small opening 8 or 10 inches square into the attic of the building. Here we lay comfortably on the sawdust covering the lath and ceiling of the room below, not realizing that the ceiling might give way and drop us down into the room below. Fortunately the ceiling held and nothing happened to us.

One of the interesting small buildings on grandfather's property was the Smoke house. This building was kept locked and we never got into it except when some adult opened it. It was a room wherein the walls were blackened by much smoke. It was used to smoke hams to give them a special flavor. Controlled smoke was admitted to the building for a definite period of time to get the meat treated long enough to attain the desired flavor.

One time I had done something wrong. I don't remember what, but my father had to punish me for it. For the purpose he wanted to use a switch. So he gave me his knife and made me go to some growing lilac bushes and cut my own switch. I don't remember the extent of the punishment but I do remember having to bring my own switch for the purpose.

I don't remember much about my brother Montie's early days. He seemed to cry a lot. I don't know whether he was unwell or not but Clifford and I were always busy with our own affairs and didn't contribute much in looking after him. I remember one time after Mama had cleaned him up and arranged his hair in long up-and-down rolls of curls she put him in a little wagon and we pulled him around the yard. Maybe Mama wanted to pretend that he was a girl for she kept his hair long and arranged in curls like a girl. Later my sister Leta was born.

18

I recall one winter we had a severe snow-storm when great banks of snow gathered and leaned high upon the walls of grandfather's farm buildings and almost completely hid the fences. Then the storm changed to sleet. When we awoke the next morning we found our undulating world of snow banks covered with a glistening cover of ice, which was strong enough to hold us up. We played and slid around on the glossy slopes. Then we found we could, with shovels, break through the crust and dig tunnels and caves under it where we played with a roof over our heads.

One bright sunny day in summer I accompanied my father and some other men as they drove grandfather's sheep down the road about a half a mile to a place where the creek curved right out to the road. Here the men stripped to the waist and took the sheep one by one into the water and washed their wool thoroughly in the running water. The sheep could not touch bottom but floated easily and their heads were kept well above the water.

A day or two later the sheep were sheared on the floor of grandfather's barn. The animals were thrown onto their sides, and the head held down by one man while another cut off the wool with huge shears that were kept very sharp. Great fleeces of wool were gathered up. When a sheep was sheared and set free she was unharmed, but she sure looked naked.

One fall Clifford and I were taken by our parents to the agricultural fair in Guelph, Ontario. We started out early one morning in a one-horse buggy. Clifford and I sat on a little bench with our backs to the dashboard and facing our parents on the seat. We were warmly dressed and comfortable but still sleepy. When we were a few miles from Courtland on Talbot Road, where we were to take the train, my father realized that we were late, and likely to miss the train. So he took out his whip and made the horse take the last mile or so on the run. Anyway, we made it. The horse was left in the livery stable and we boarded the train. I don't remember much about the fair, but my father, being a farmer, had much to learn because Guelph was the center of Ontario's farm industry, and they had an agricultural college there. I do remember the antics of some clowns and the horse-races. When it was time to eat, great numbers of people sat on the grass and opened their food baskets and had their picnic lunches. When looking at the farm animals we came to a high enclosure which contained a huge bull. I remember standing on the railing of the cage and looking up at an enormous animal which seemed to tower over me.

I didn't see much of my Uncle John, who owned and operated the farm north of Grandpa Park's. He was a good farmer and took pride in his fine horses. He was much bigger than my father, as I particularly noted when he pulled a baby tooth for me with dental forceps.

One story about Uncle John which I remember hearing indicated how strong he was. A number of men were having a competition of strength on the wharf at Pt. Burwell, with Uncle John among them. They finally came to a ships anchor which weighed 700 pounds. My Uncle John was the only one who could lift it free of the floor.

One time when visiting at Grandpa Cutler's I remember standing by a small iron gate which was covered with hoarfrost. I thought it would be nice to lick it off with my tongue. At the first touch of my tongue it froze fast to the iron gate. It took a little while for my body heat to warm the iron sufficiently to free my tongue.

19

CHAPTER FOUR

LATER PRESCHOOL YEARS

When I was still too young to go to school we moved from grandfather Park's farm into the corner house in Fair Ground, where my grandfather Cutler had been living. By this time grandfather Cutler had built a concrete block house for himself a few hundred feet to the west, next to the Methodist Church, where he and grand mother Cutler now lived. Grandmother Cutler was suffering from heart trouble and was no longer able to take care of the corner house, which served as a stopping place for the few travelers who came through Fair Ground.

After we moved in, I remember visiting grandma and grandpa Cutler in their new home. It was very comfortable and pleasant. Grandma Cutler was a stoutish woman and not very tall. At that time her own mother, my great grandmother Edmonds was with her. She too was built like her daughter, my grandmother Cutler. There was a piano at one end of the room, and over the piano was a huge picture of grandfather and grandmother Cutler. I don't remember much about my grandmother Cutler. I suppose because she was not well I didn't see much of her. She died of heart trouble at 56 years of age.

My grandmother Cutler had a sister Mary who was married to Ben Purdy. They lived about two miles west of Fair Ground. She was my mother's Aunt Mary and we also called her Aunt Mary. She was not well either, but she was a fine Christian woman and a member of the Free Methodist Church, which was near to her house. Her husband Ben, however, was somewhat shady in his dealings, although he too was a Free Methodist.

Grandmother Cutler's brother George Edmonds was the youngest of her family. He lived on the Edmonds homestead a few miles away, north of Kinglake. His home was in a pine forest. He was my mother's Uncle George and we also called him Uncle George. He had a small mill where he made pumps, using the pine trees of his forest. These of course were wooden pumps but they functioned very well, and he had a good business selling and installing them around the country. When he passed through Fair Ground he always stopped and stayed overnight at our place. He was a pleasant bald-headed man. He was nice to us children, and we were always much amused at the way he would wiggle his ears for us. George Edmonds had three children, Cora, Orlaf and Allie. Orlaf was quite deaf. We used to see these cousins of mother's occasionally.

Our home on the corner was quite a sizable structure. It had a concrete area about eight feet wide which went across the whole north side of the house. ft was up about two feet off the ground, to accommodate the traveling clientele with horse- drawn buggies and democrats. There was a central doorway opening into a hall, and stairwell leading to the upstairs. At the eastern side of the hall entrance was a small room where travelers could sit together and talk and smoke. Behind this was my father's and mother's bedroom. On the opposite side of the hallway entrance was a large dining room where the guests and boarders were fed. Upstairs there were four bedrooms and a comfortable sitting room, chiefly for the female guests. At the head of the stairs, on the second floor, was a considerable space which my

20

father used for his barbershop. From this area a door opened onto an upstairs porch which was about eight by ten feet in size with a railing around it. It was supported on the roadside by two sturdy posts, which went down to the concrete platform below. All of the above mentioned area was for the use of paying guests.

The rest of the house extending backwards toward the south was our family living quarters. The first was a large room, in which there was a large wood-burning cookstove. This room also served as a dining room for the family. Behind this large room was another bedroom and a pantry. Upstairs in this part, with its own stairway, were three bedrooms with a hallway large enough for a fourth bed. Up here is where we four children slept and also the hired girl whom my mother used.

One intriguing place for us children was a large clothes closet under the front stairway. It was dark and narrow and opened only into our living quarters. From our kitchen-living room, another building was attached to the house, on the west side. This was a large poorly-constructed building, which was more of a woodshed than living quarters. However, it was used in the summer time for cooking and our eating of meals.

Just to the west of the above building-complex was another separate large two-story building, which was used as rented quarters for families or boarders. During the days when the sawmill was operating full blast, all of these accommodations were occupied, mostly by people working at the mill. Most of them were served in the large dining room where two long tables went the full length of the room. You can visualize how busy my mother was cooking for all of these people.

There was no inside plumbing but there were two outside toilet buildings on the property. There was a good well just outside of the fence, actually on the road, with its trough for watering horses. There was also a large cistern close to the main house, where water was collected off the roofs of the large buildings. Mother had a big sink where she could wash vegetables and dishes with the water running through a large drainage system into the sandy soil.

The large rooms had their own wood stoves. The upstairs rooms were mostly unheated but did get some heat from the rooms below through doorways or openings in the floor through the ceiling of rooms below. In our early days there, the only source of light, at night, were kerosene lamps.

There was no electricity and no refrigeration. Mother did, however, have a cold box which was kept cold by huge chunks of ice which my father brought in regularly from his winter hoard of ice blocks, buried in sawdust in his ice house.

Potatoes and some other vegetables were kept in an underground root-cellar. There were large bins of them in this huge dark place, entered by stairs leading down into it through a heavy insulated door. This whole grotto was covered over by a large mound of earth about 50 feet to the south of other buildings. This home, on the corner, was where I lived from four or five years of age until I started to university at age 20.

When we first moved into this property, my grandfather Cutler still maintained, on the back of the lot, about six or eight beehives. We of course were wisely kept away from the bees. But we liked to look at them, as they went on their busy lives

21

of going and coming in huge numbers, as they gathered honey. We watched too when they swarmed. At this time they hung in a huge clump, usually. on a low branch of a nearby tree. The clump of bees clinging to each other was about five inches across at the branch level, and hung down in a cluster of bees about six or seven inches deep. To keep them from getting away, grandpa Cutler dressed himself in thick clothing, with a straw hat on his head. Over his hat and his face down around his shoulders, he had on a large piece of fine net, which the bees could not get through. Over his hands he had heavy gloves, with ties around his wrists so the bees could not get inside his clothing. Dressed like this, he calmly and slowly approached the clump of bees, carrying a new empty hive, open at the top, and carefully shook the bees down into it. When all of the bees were in it, he put on the cover and placed it with the other hives. So long as the queen bee was with them the bees stayed together. When the queen bee found herself in a new spacious hive, she promptly set up housekeeping, and the other bees started to gather more honey.

In the process of gathering the honey from the hives, grandfather dressed as above and forced smoke from a gadget into the hive, and when the bees were stupefied by it he took out the full honey sections and supplied the bees with new foundations, on which they could build more honeycombs.

To the west of the houses on the corner already mentioned and east of grand father Cutler's new house farther to the west was a large barn. The ground floor of this barn opened directly onto the road, because it served as a livery stable. There were several stalls for the horses of traveler-guests and shelter for their vehicles. Above, and attached on the south side of it, were mows for hay and straw. There was also a granary on the ground floor which contained oats for the horses. Farther back on the ground-floor level was space for farm cows and pigs and a larger granary. There was also a fenced-in space for the cattle and pigs which allowed them to be outside.

Between our houses and the barn was a row of black currant bushes and a red cherry tree. The soil was sandy and weeds were plentiful, among them catnip, horehound, burdock and hemp. My father allowed his fattening pigs to have the run of this area. I remember, on one hot summer day, one of these fat pigs was not as lively as the others, so it was easy for me to climb onto its back. For a little while I rode around thus, with the pig puffing from the heat. After I tired of it, the pig lay down in the sand next to the house. The next morning that pig was found there dead.

When the cherries were red in the cherry tree, one day Clifford and I were up in the tree stuffing ourselves. While there, I discovered it was no trouble to swallow the cherry pit. From that day on I had no trouble swallowing pills.

During those boyhood days we needed some simple toys to amuse us, so my father made us some tops. They were fashioned out of empty spools, which were plentiful in those days and had deeper flanges than in modern days. From one empty spool he made two tops by cutting it in two and fitting short pieces of wood into the holes, and shaping the inside end of the sticks and spools to a point. We spent long hours spinning them. He also made us fine spinning wheels, by threading strong cord through two of the holes in large coat buttons. We learned to wind these up in the center of the double cords and made them spin so fast that they would wind themselves up for a reverse spin when we pulled the ends apart and relaxed and pulled them alternately.

22

Every once in a while a peddler would come along with his heavy suitcase packed with things to sell. We were always on hand to look at his fascinating wares. They included such things as thread, needles, pins, combs, buttons, eye glasses, all kinds of trinkets and cheap jewelry, etc.