by Betty Ponder

By now they had been married three years and a first medical position materialized. Wilford was offered a job working with Dr. Alexander in Tillsonburg, an unchanging village of perhaps three thousand people set on the flat lands of Southern Ontario. He hoped to become a partner and was sent off to school again in Toronto to learn the mysteries of eye-glass fitting so the office equipment could be used to its fullest. He bought his first car, an unidentifiable model from the photo, his foot placed on the running board to signify ownership. On his return a few months later he found that the envisioned partnership had been sold to a country doctor living in Brownsville, a cross-roads village six miles away. So he began again, this time buying the country practice left vacant in that small village with hospital privileges in Tillsonburg. Wilford was on his own and Lila was pregnant. He opened his office on September 1st, 1929, eight weeks before the great stock market crash. My mother miscarried her first baby.

With the practice came a white clapboard house with a ready made office with slippery black horse-hair covered furniture in the waiting room. The examining room had an operating table with extendable pieces at both ends, lots of shining tools behind glass doors, and a sink. Strangely, though, in the beginning there was no running water, only a pump which, when primed, gushed water from the outside deep well or perhaps from the cistern in the basement. The barn down the lane at the back corner of the tree- and rose-covered lot housed two horse drawn sleds and an ancient carriage. Most wondrous of all, there was a hay-mow, much beloved by village children as a trysting place for innocent sexual experimentation.

Immediate additions were made to the office. A sun-reflecting plaque with name and prominent M.D. was affixed to the front entry; a shouting tube was run from the front door to emerge near a sleeping ear in the upstairs bedroom; drugs, small vials, microscopes and Bunsen burner were added to make up the dispensary. Mrs. Jacobs in the village was hired to wash bloody towels and bandages in her home and a man who was mentally challenged was hired to mow the lawns.

Most necessities including groceries, boots, meat and postal stamps could be purchased from a building across the road, set high on its basement to accommodate a wagon loading platform. The villageís verandahed clapboard and yellow brick homes backed onto fields of corn and fat cows who contributed to the dairy, which nestled concrete-cool and sweet-creamed by the stream. Snakes lived along the stream as well, copper-heads and puff-adders.

There were two churches, religion being the hub

around which the village turned. The roads out led

nowhere in particular and there was no money.

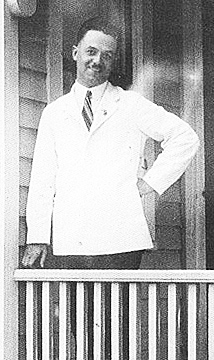

Dr. Wilford Park, first opening first office in Brownsville, 1929

There were few patients. Those remaining

loyal to the original doctor followed him the six miles

to Tillsonburg if transportation was possible. So at

first it was emergency work primarily, farm accidents,

cuts to be stitched and broken bones to be set, held

firm with plaster of Paris, and ear aches through the

black nights pulsing with blood rhythms, and the

untimely bleeding of women and the awesome

parasites. To reach the village switchboard, phones

were cranked and receivers lifted along the lines to

pass along urgency. Some came running or by wagon

and the doctor made house calls, often with Lila in

those early years, she to gentle and comfort as

Wilford went about the business of repairing.

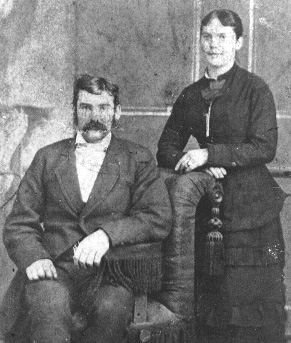

Joseph and Emily Jane Marshman, married 1877, parents of Lila

It was in April of their first year in the village that Lilaís grandmother on her motherís side, Emily Marshman, died on her farm near Fairground. Death occurred at home with dignity in those days, though not always with understanding. The family, reconciled to the inevitable, was present, mourning in each otherís arms and comforting one another with assurances of heaven. Emily was small and dark and had those high cheek-bones which have been passed through four succeeding generations, a sort of tribal marking. She died of diabetes and cancer my Aunt Orpha told me many years later. Not so, according to my father. He was with her when she died and said that she died of heart problems.

I was conceived in late October of that year, before the frost, when the wild blue asters bloomed. I see my first pictures, occupying my space inside my motherís swollen tummy. My father wrote small poems to me, hoping I would be a girl, a replica of my mother or so he told me later. With the first stirring of life she must have remembered the one miscarried, and grieved for the unrecognized lost one, as all mothers grieve for such losses.

A new car arrived before I did, a Dodge-six is pictured on the first of July, square nosed and pop- eyed bearing the license plate D (for doctor) and the inauspicious numbers 996. The labeling of doctorís plates was discontinued in later years resultant to thefts of the drug laden black bags carried by working physicians at all times. I arrived a few weeks later, and judging from the string of proud pictures, I was much admired. They called me Betty, perhaps without realizing it was the fashionable name currently in vogue on the screen. Many girls in my generation seemed to be named Betty. Within the year my mother was again pregnant, and spring spilled into summer.

Then the breezes shimmied the purple vetch and bees hummed, prowling the buttercups. And sometimes blackened half-skies to the west grew into churning pyramids boiling and reaching for the stratosphere. And so the bees hurried on prodded by heat and pressure changes.

My father kept bees. Between patients he could be seen in his bee-keeperís head-net and his smoke-can poking and prodding; the colony was never quite sure what to expect. However, he knew the garden well. Wild yellow rose bushes clung to the wooden fence that skirted the lane and grape vines wove solid the long bower leading to the outhouse, their notched flat leaves cool against the sun and mysterious in the night. The vegetable garden was examined and tended with care: potatoes and corn were hilled; bugs were picked off leaves and stems; and the hoeing was sure and accurate, skillful in its search for intrusion, slicing at an angle to rough the soil in tune with rhythms of the heart. Wilford had his hoe in his hand the day Lila cried out for him to come.

My doll and I were sitting in the sun on the concrete walkway leading to the grape arbour; we were reaching for dandelions. My mother was poised in the doorway when I heard that primitive cry of fear, low and unmistakable in its demand for me not to move and for my father to come. I saw then what my mother had seen. Two puff adders coiled and upright, heads balanced broad like cobras, waited under the edge of the porch. They looked down on me and at my father approaching and they arched and swayed a little then, motionless they remained, accepting the first blows with quiet resignation as though mesmerized. He killed them there, hacking and slashing with the hoe as they coiled and undulated round the handle. There was no sound as they curled and died. I knew they died, that life was gone, had been taken as he carried them away to be buried, swinging limp like pendulums. I knew it in every cell of my body and my fear for myself and the acknowledgment of the sureness of the fates was changed forever. My terror of snakes became almost pathological.

My brother, Douglas was born in the winter, a strange pixy creature with large ears, resembling no one. I thought him passable and he didnít cry much. The family rejoiced in the new arrival. My motherís large family of sisters visited often, and in the spring a niece, Maxine came to live and to help while attending the local school. The dog and the cat and the expanding family hummed with a kind of happy frenzy. Plans were made to celebrate my third birthday. A wicker doll carriage just my size to push, and a huge doll were purchased and hidden away and my mother anticipated my delight as she brushed my hair from my face in the mornings to be caught in an oval clip with ribbons. Doctoring continued at a goodly pace. Babies were born in the homes in the village. Many of them were named Wilford, after my father.

The dangers of childbirth were such that each new arrival and survival cemented a close bond between doctor and mother. He was proud of this in a withdrawn way, tipping his hat when he met an acquaintance but hurrying on sometimes glancing back, never stopping for small talk. He didnít know how to talk small talk.